Court’s decision

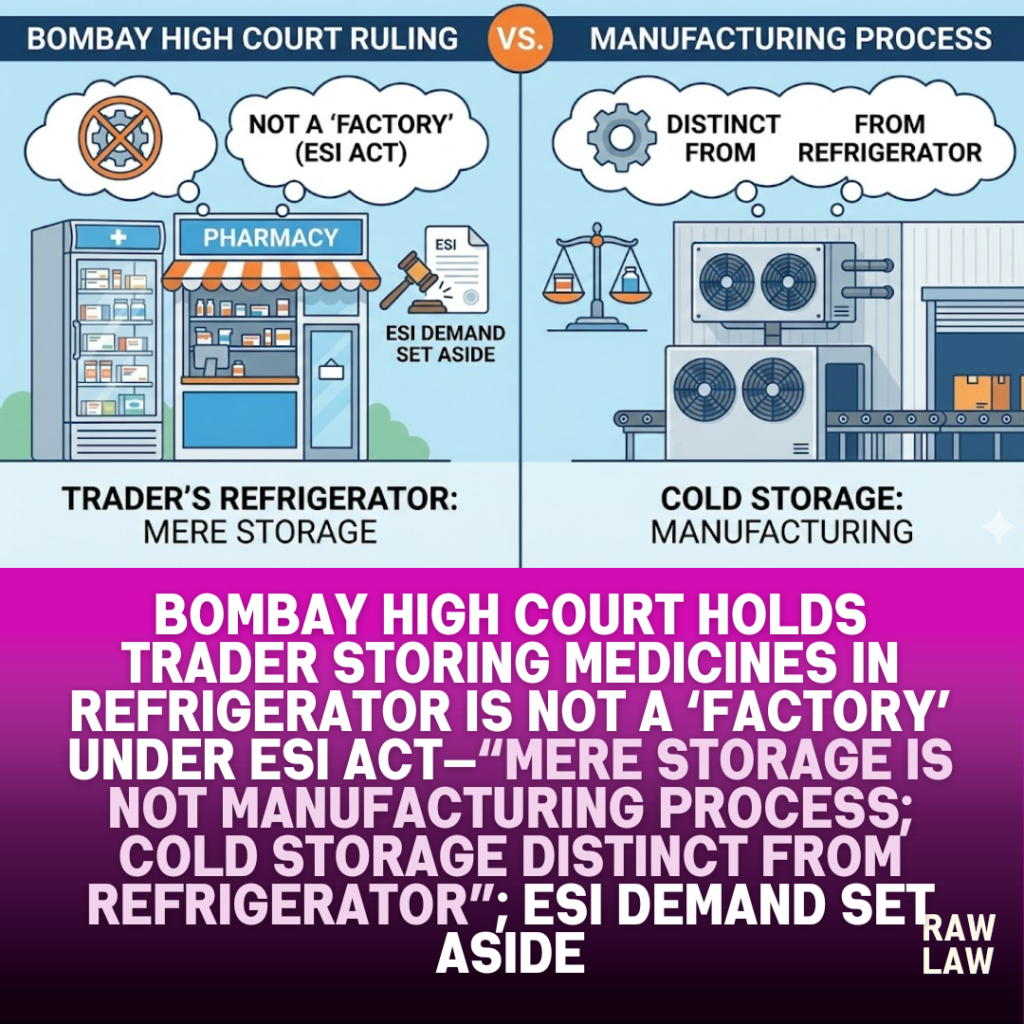

The Bombay High Court allowed a first appeal under the Employees’ State Insurance Act, 1948, and set aside the ESI Court’s finding that a medicine distributor storing drugs in a refrigerator was engaged in a “manufacturing process”. The Court held that mere storage or preservation of medicines in a refrigerator by a trader does not amount to a manufacturing process within the meaning of the Factories Act read with the ESI Act. It ruled that Section 2(k)(vi) of the Factories Act contemplates a “process for” preserving or storing in cold storage, not the mere act of storage, and further clarified that a domestic refrigerator cannot be equated with a cold storage. Consequently, the appellant was held not liable to be covered under the ESI Act.

Facts

The appellant was a distributor and trader of medicines for various pharmaceutical companies. It purchased finished medicines from manufacturers and sold them onward to chemists and druggists. For maintaining quality, the medicines were stored in a refrigerator until sale. There was no dispute that the appellant did not manufacture medicines, alter them, re-pack them, or subject them to any treatment or activity after purchase.

Proceedings were initiated by the Employees’ State Insurance Corporation contending that storage of medicines in a refrigerator amounted to continuation of the manufacturing process. Accepting this contention, the ESI Court held that preservation and storage of medicines constituted a manufacturing process, thereby attracting the definition of “factory” under Section 2(12) of the ESI Act and fastening contribution liability on the appellant. Aggrieved, the appellant preferred a first appeal before the High Court.

Issues

The substantial question of law framed by the High Court was whether the use of a refrigerator for storage of medicines amounts to continuation of the manufacturing process so as to bring the establishment within the ambit of the ESI Act. Allied issues included the correct interpretation of “manufacturing process” under Section 2(k)(vi) of the Factories Act, the distinction between “cold storage” and a refrigerator, and whether incidental storage by a trader could be treated as a dominant manufacturing activity.

Appellant’s arguments

The appellant argued that it was purely a trading establishment and did not engage in any manufacturing activity whatsoever. It was submitted that medicines were fully manufactured products when purchased from pharmaceutical companies and no further process was carried out by the appellant. Mere storage in a refrigerator, without any activity or treatment being performed on the goods, could not be equated with a manufacturing process.

Relying on multiple judicial precedents, the appellant contended that the concept of extension of manufacturing process had been wrongly applied by the ESI Court. It was also argued that Section 2(k)(vi) of the Factories Act refers specifically to “cold storage”, which is materially different from a domestic or commercial refrigerator used for limited storage purposes. Therefore, the ESI Act was inapplicable.

Respondents’ arguments

The ESI Corporation argued that the definition of “manufacturing process” under the Factories Act is wide and includes “preserving or storing any article in cold storage”. It was contended that preservation itself amounts to a manufacturing process and that the Act, being a welfare legislation, ought to be interpreted expansively to extend coverage.

The respondents submitted that manufacturing need not result in a new product and that maintenance or preservation of an existing product also falls within the scope of manufacturing. According to the Corporation, storing medicines in a refrigerated environment directly facilitated their use and sale and therefore constituted a manufacturing process.

Analysis of the law

The High Court undertook a detailed analysis of the statutory scheme. It examined Section 2(12) of the ESI Act defining “factory”, Section 2(14-AA) of the ESI Act which adopts the definition of “manufacturing process” from the Factories Act, and Section 2(k) of the Factories Act, 1948.

The Court emphasised the significance of the phrase “any process for” used in Section 2(k). It held that the legislature consciously used the words “process for preserving or storing” and not “process of preserving or storing”. This linguistic distinction, according to the Court, creates a condition precedent: there must be some process or activity carried out on the goods for the purpose of preservation or storage. Mere passive storage does not satisfy this requirement.

Precedent analysis

The Court relied on Supreme Court jurisprudence, including the decision in Delhi Cold Storage Pvt. Ltd., to underscore that mere storage resulting in incidental changes does not amount to a “process”. The High Court also examined and relied upon earlier decisions of various High Courts distinguishing cold storage facilities from refrigerators and holding that traders merely storing goods do not carry on manufacturing processes.

The Court distinguished decisions relied upon by the ESI Corporation which proceeded on the premise that mere preservation constitutes manufacturing, noting that those judgments did not analyse the phrase “any process for” in depth.

Court’s reasoning

Applying these principles, the High Court found that the appellant carried out no activity whatsoever on the medicines after purchase. There was no evidence of any process being undertaken prior to or during storage. The appellant’s dominant activity was trading, and refrigeration was only incidental to that activity.

The Court further held that a refrigerator of limited capacity cannot be equated with a “cold storage” facility as contemplated under Section 2(k)(vi) of the Factories Act. Cold storage refers to a specialised, large-scale, scientifically controlled facility, whereas a refrigerator is a common appliance used for temporary storage.

The Court rejected the argument that welfare legislation must automatically be interpreted to cover all activities. It held that unless the statutory ingredients are satisfied, coverage under the ESI Act cannot be extended merely on equitable considerations.

Conclusion

The Bombay High Court concluded that the appellant’s establishment did not satisfy the definition of a “factory” under the ESI Act, as no manufacturing process was carried on. The mere act of storing medicines in a refrigerator by a trader does not constitute manufacturing. The appeal was allowed, the question of law was answered in favour of the appellant, and the ESI demand was set aside, though the operation of the judgment was stayed for eight weeks.

Implications

This judgment provides important clarity for traders, distributors, and commercial establishments dealing with perishable or temperature-sensitive goods. It draws a clear line between manufacturing activity and incidental storage, preventing unwarranted extension of ESI liability to pure trading entities. The ruling also underscores that beneficial legislation, while interpreted purposively, cannot be stretched beyond statutory language. It is likely to have significant impact on ESI enforcement actions against pharmaceutical distributors and similar businesses.

Case law references

- Delhi Cold Storage Pvt. Ltd. v. Commissioner of Income Tax: Held that mere storage does not amount to a “process” in the absence of active treatment of goods.

- Unity Traders v. Regional Director, ESI Corporation: Distinguished cold storage from ordinary storage for the purpose of ESI applicability.

- The Management of Kumar Medical Centre v. Employees’ State Insurance Corporation: Held that traders storing medicines are not engaged in manufacturing.

- Hotel New Nalanda v. Regional Director, ESI Corporation: Reiterated limits of extension of manufacturing process doctrine.

FAQs

Does storing medicines in a refrigerator attract ESI Act coverage?

No. Mere storage of medicines in a refrigerator by a trader does not amount to a manufacturing process under the ESI Act.

Is refrigeration the same as cold storage under the Factories Act?

No. Cold storage refers to specialised facilities, whereas a refrigerator is a common appliance and does not fall within Section 2(k)(vi).

Can ESI Act be applied to traders on welfare grounds alone?

No. Even welfare legislation applies only when statutory conditions are satisfied; incidental activities cannot trigger coverage.