1. Court’s decision

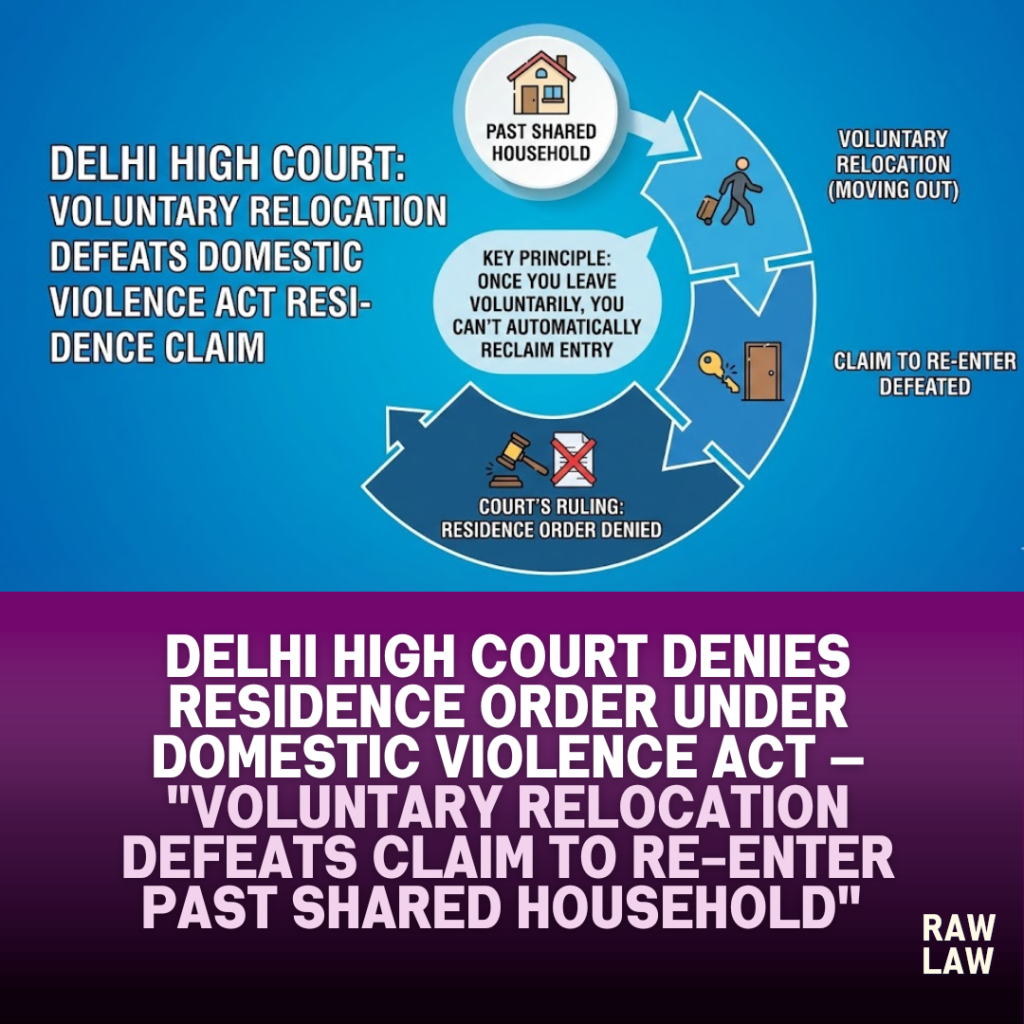

The Delhi High Court dismissed a criminal miscellaneous petition filed by an elderly wife challenging concurrent orders of the Magistrate and Sessions Court refusing her re-entry into the Green Park house claimed as a shared household. The Court held that where an aggrieved woman voluntarily and consciously shifts to alternate accommodation of the same standard owned by the husband, the Domestic Violence Act does not confer an indefeasible right to return to a previous residence. The Court ruled that the statute is protective, not proprietary, and cannot be used to convert a property dispute into domestic violence litigation.

2. Facts

The petitioner married the first respondent in 1964 and lived for decades in a house at Green Park, New Delhi, where their children were raised. In April 2023, she shifted with her belongings to her daughter’s house at Safdarjung Enclave for medical treatment and post-surgery care. Later, when she attempted to return to the Green Park premises in July 2023, she alleged that she was denied entry. Claiming emotional and economic abuse, she invoked proceedings under the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005 and sought a residence order under Section 19 directing restoration to the Green Park house.

3. Issues

The principal issues were whether the Green Park premises continued to qualify as a “shared household” under Section 2(s) of the Domestic Violence Act, whether denial of re-entry amounted to domestic violence in the nature of economic abuse, and whether the petitioner was entitled to a residence order despite having shifted to and continued residing in an alternate accommodation owned by her husband.

4. Petitioner’s arguments

The petitioner contended that she had lived in the Green Park house for nearly sixty years and that her departure in April 2023 was purely temporary for medical reasons. She argued that her exclusion thereafter rendered her shelter-less and violated her statutory right to reside in the shared household. It was submitted that the courts below erred in holding that alternate accommodation at Safdarjung Enclave satisfied the husband’s obligation, particularly when the property was allegedly not in his actual possession and was subject to disputes involving the daughter.

5. Respondents’ arguments

The respondents asserted that the petitioner voluntarily left the Green Park premises and established a settled residence at Safdarjung Enclave, which undisputedly belonged to the husband. They argued that there was no forcible dispossession or coercion, that the petitioner consistently described Safdarjung Enclave as her residence in pleadings and police complaints, and that the Domestic Violence Act was being misused to advance an inter se family property dispute. It was emphasised that the husband had no objection to her continuing to reside at the Safdarjung property.

6. Analysis of the law

The Court analysed Sections 2(s), 17, and 19 of the Domestic Violence Act, reiterating that the right to residence is meant to ensure that an aggrieved woman is not rendered roofless. The statute does not guarantee a right to insist upon a particular property when suitable alternate accommodation of the same standard is available. The Court emphasised that the concept of a shared household is fact-sensitive and must exist in presenti, not merely as a matter of past residence.

7. Precedent analysis

Relying on Satish Chander Ahuja v. Sneha Ahuja, the Court held that while the definition of shared household must be interpreted broadly, it does not mean that every house where the wife once lived remains a shared household in perpetuity. The Court also followed Ajay Kumar Jain v. Baljeet Kaur Jain, which held that a wife cannot insist on living in a particular property if the husband offers a suitable alternative matrimonial home.

8. Court’s reasoning

The Court found that the petitioner herself repeatedly described Safdarjung Enclave as her residence in pleadings and police complaints, and even affixed her nameplate there, indicating a conscious relocation rather than temporary displacement. There was no material to show forcible eviction or coercion from the Green Park house. The Court held that compelling restoration would disturb settled possession of other occupants and stretch the DV Act beyond its legislative intent. The relief under Section 19 being discretionary and equitable, denial was justified in the facts.

9. Conclusion

The Delhi High Court upheld the concurrent findings of the courts below and dismissed the petition. It held that the petitioner was not roofless, that the statutory object of the Domestic Violence Act stood satisfied through availability of alternate accommodation, and that no perversity or illegality warranted interference under inherent jurisdiction.

10. Implications

This judgment draws a clear boundary between residence rights and property rights under the Domestic Violence Act. It reinforces that voluntary relocation to alternate accommodation can defeat claims for restoration to an earlier residence and that the Act cannot be invoked as a tool to reopen settled residential arrangements or pressurise parties in property disputes.

Case Law References

- Satish Chander Ahuja v. Sneha Ahuja – Clarified that a shared household must subsist in presenti and is not perpetual merely due to past residence; applied by the Court.

- Ajay Kumar Jain v. Baljeet Kaur Jain – Held that a wife cannot insist on residing in a particular property when suitable alternative accommodation is offered; relied upon.

- R.K. Vijayasarathy v. Sudha Seetharam – Reiterated limits on inherent jurisdiction and cautioned against misuse of criminal proceedings.

FAQs

Q1. Can a wife insist on returning to a house she earlier lived in under the Domestic Violence Act?

Not automatically. If she voluntarily shifted and has access to suitable alternate accommodation, courts may deny restoration.

Q2. What is meant by “shared household” under the Domestic Violence Act?

It is a household where the parties live or have lived together in a domestic relationship, but it must subsist in the present and is determined on facts.

Q3. Does the Domestic Violence Act decide property ownership disputes?

No. The Act is protective and remedial; it does not confer ownership rights or resolve property disputes.