Court’s Decision

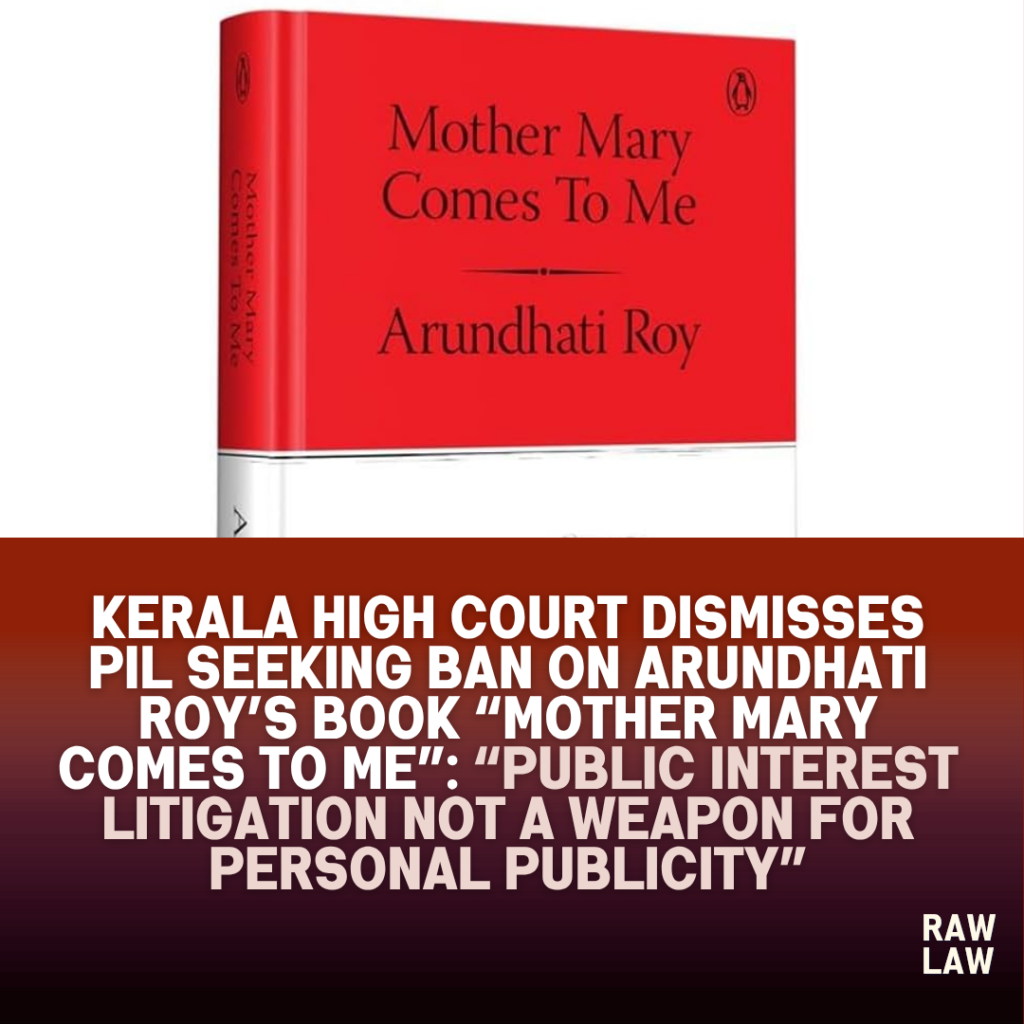

The Kerala High Court, speaking through Chief Justice Nitin Jamdar and Justice Basant Balaji, dismissed a Public Interest Litigation (PIL) seeking to ban the sale and circulation of author Arundhati Roy’s book “Mother Mary Comes to Me” on the ground that its cover depicting the author smoking violated the Cigarettes and Other Tobacco Products Act, 2003 (COTPA).

The Court held that the depiction of smoking on a book cover did not constitute an advertisement or promotion of tobacco products under Section 5 of COTPA. The bench further ruled that the matter, if at all, fell within the jurisdiction of the Steering Committee established under the Act and not within the extraordinary jurisdiction of the Court.

The PIL was declared frivolous and motivated, with the Court observing that:

“Public interest litigation is a weapon which has to be used with great care and circumspection… It should not be used for suspicious products of mischief or for cheap popularity.”

The Court strongly admonished the petitioner, an advocate, for filing the petition without proper research, without examining the book, and without approaching the competent authority, calling it an abuse of judicial process.

Facts

The PIL was filed by a practicing advocate who sought directions against the Union of India, Press Council of India, State of Kerala, Penguin Random House (publisher), and Arundhati Roy (author), alleging that the book cover showing the author smoking a cigarette violated the COTPA, 2003.

The petitioner claimed that such a depiction amounted to indirect advertisement of tobacco products under Section 5 and was prohibited by law. It was also argued that the depiction required statutory health warnings as mandated for films, television, and advertisements involving tobacco.

The book “Mother Mary Comes to Me” was released on 2 September 2025, and the petitioner annexed only a photo of the cover and a copy of the COTPA Act as evidence, without any reference to the statutory rules, notifications, or disclaimers.

Issues

- Whether the depiction of smoking on the cover of a literary book violates Section 5 of the Cigarettes and Other Tobacco Products Act, 2003?

- Whether the PIL is maintainable when a specialized expert authority — the Steering Committee — exists to examine such alleged violations?

- Whether the PIL amounted to misuse of judicial process filed for publicity rather than genuine public interest?

Petitioner’s Arguments

The petitioner argued that the depiction of smoking on the book cover violated the prohibition on indirect advertising under Section 5 of COTPA, 2003. He contended that such imagery promotes smoking and sends an inappropriate message to the public.

He further argued that Sections 7 and 8 of the Act, which mandate health warnings, were also applicable. Since the publication was in the public domain, the authorities were duty-bound to act against the publisher and author.

The petitioner urged the Court to direct the withdrawal of all copies of the book and prohibit its sale, circulation, and display across the country.

Respondent’s Arguments

The Union of India clarified that under Section 25 of the Act and Rule 4 of the Cigarettes and Other Tobacco Products Rules, 2004, a Steering Committee had been constituted to handle complaints of violations under Section 5. Any citizen could lodge a complaint, and the Committee was empowered to act suo motu or after hearing both sides. The petitioner had not approached this forum.

Penguin Random House, representing the author, argued that the petitioner suppressed key facts, including the disclaimer printed on the book’s back cover stating that the depiction was “not intended to promote smoking.”

They contended that Section 5 applied only to persons engaged in the trade or advertisement of tobacco products, not to artistic or literary expression. Furthermore, Sections 7 and 8, dealing with health warnings, applied to cigarette packaging, not printed books.

The publisher accused the petitioner of filing the PIL for cheap publicity, infringing the fundamental rights of the author and publisher under Articles 19(1)(a) and 19(1)(g) — the rights to freedom of expression and trade.

The respondents also cited precedents including:

- K.A. Abbas v. Union of India (1970) 2 SCC 780 — upholding artistic freedom and reasonable censorship in films.

- Mahesh Bhatt v. Union of India (2009 SCC OnLine Del 104) — recognizing creative freedom in cinematic expression.

- Shreya Singhal v. Union of India (2015) 5 SCC 1 — reinforcing the constitutional protection of free speech.

- Ramanathan v. State (2023 SCC OnLine Mad 4522) — applying proportionality to restrictions on expression.

Analysis of the Law

The Court analyzed Sections 3, 5, 7, and 8 of COTPA, 2003, along with the Rules of 2004, and noted that:

- Section 5 prohibits advertisements of tobacco products, not all depictions of smoking.

- The term “advertisement” under Section 3(a) requires an intent to promote the use or consumption of tobacco.

- There is no legal requirement for health warnings on images in printed materials such as books.

The Rules of 2004 define indirect advertisement narrowly, linking it to commercial promotion of tobacco products. The Court concluded that a literary cover image could not be equated to such promotion, particularly when accompanied by a disclaimer.

Moreover, the Steering Committee established under Rule 4(9) was found to be the appropriate expert forum to examine potential violations of Section 5, consisting of senior officials, medical experts, and representatives from public health, media, and law.

Precedent Analysis

- Dattaraj Nathuji Thaware v. State of Maharashtra (2005) 1 SCC 590 — The Supreme Court warned against abuse of PILs for publicity or personal vendetta.

Reference: Relied upon to dismiss the petition, emphasizing that PILs must not become tools of self-promotion. - K.A. Abbas v. Union of India (1970) 2 SCC 780 — Affirmed the necessity of balancing creative freedom and public decency.

Reference: Cited by the publisher to uphold the author’s artistic rights. - Shreya Singhal v. Union of India (2015) 5 SCC 1 — Struck down vague restrictions on free speech.

Reference: Used to stress that Section 5 of COTPA cannot be interpreted to curb protected artistic expression. - Mahesh Bhatt v. Union of India (2009 SCC OnLine Del 104) — Recognized the importance of creative autonomy in visual and literary arts.

Reference: Supported the view that the Act regulates trade promotion, not literary representation.

Court’s Reasoning

The Bench strongly criticized the petitioner’s lack of research and factual misstatements. It noted that the petition contained no reference to statutory rules, notifications, or the disclaimer printed in the book, and that the petitioner admitted to not having read the book before filing the case.

The Court remarked:

“Such a cavalier approach is wholly unsatisfactory. Greater diligence and responsibility was expected, particularly in a petition filed by an advocate.”

On maintainability, the Court held that the existence of a specialized expert mechanism under the Act made the PIL unsustainable. The petitioner failed to establish why he bypassed this remedy.

It reiterated that personal moral perceptions cannot dictate statutory interpretation, and that allegations of violation must be tested objectively, not emotionally.

The Court further observed that PIL jurisdiction cannot be exploited for “intellectual arrogance” or self-promotion, noting that public interest cannot be invoked to curtail constitutionally protected creative freedom.

Conclusion

The Kerala High Court dismissed the PIL in its entirety, holding that:

- The depiction of smoking on the book cover did not amount to an advertisement under Section 5 of COTPA.

- The petitioner should have approached the Steering Committee, the designated expert body, rather than filing a PIL.

- The petition reflected misuse of judicial process and suppression of facts.

The Court concluded that:

“Public Interest Litigation is a potent tool for social justice but cannot be misused as a vehicle for self-publicity or personal vendetta.”

No costs were imposed, but the Bench issued a strong caution against frivolous petitions that distort the spirit of PIL jurisdiction.

Implications

This judgment reinforces that artistic freedom under Article 19(1)(a) cannot be curtailed merely on subjective moral grounds. It underscores the judicial intolerance for misuse of PILs, especially by legal practitioners who should act with responsibility.

The ruling clarifies that COTPA targets commercial tobacco promotion, not creative expression in literature or art. It also reaffirms that complaints under such statutes must first be placed before the expert administrative mechanism established by law.

FAQs

1. Can a book cover showing smoking be banned under COTPA, 2003?

No. COTPA prohibits advertisements and promotions of tobacco products, not artistic depictions, especially when no intent to promote smoking exists.

2. Who can handle complaints about alleged tobacco advertising violations?

The Steering Committee under the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare is the competent authority to examine violations under Section 5 of COTPA.

3. What did the Court say about misuse of PILs?

The Court reiterated that PILs must serve genuine public interest and not be used for “cheap popularity, personal vendetta, or publicity-seeking.”