1. Court’s decision

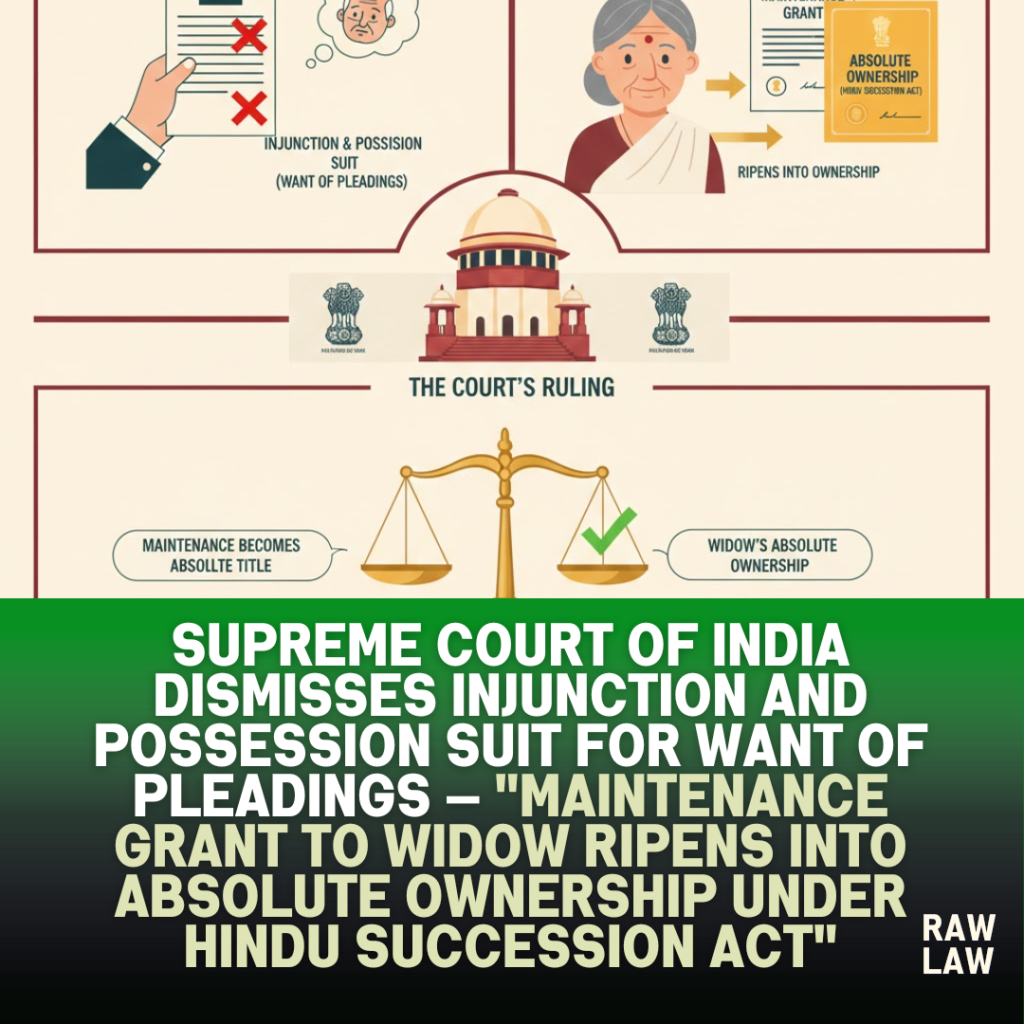

The Supreme Court of India dismissed a civil appeal arising from Himachal Pradesh, affirming the High Court’s reversal of a decree in favour of the plaintiff. The Court held that a suit for perpetual injunction and alternative recovery of possession must stand or fall on precise pleadings and proof of possession or dispossession. It further upheld that land granted to a Hindu widow in lieu of maintenance constitutes a pre-existing right that ripens into absolute ownership by virtue of Section 14(1) of the Hindu Succession Act, 1956.

2. Facts

The litigation traces back to a suit instituted in 1990 by a landholder seeking a perpetual injunction against alleged interference over agricultural land in Village Lohara, District Una. The plaint was later amended to add a prayer for recovery of possession. The defendants resisted, asserting possession through a widow whose husband had died decades earlier. According to the defence, the widow’s father-in-law, acting as karta, had placed her in enjoyment of the suit land in lieu of maintenance, and such right had matured into full ownership after 1956. The Trial Court dismissed the suit; the First Appellate Court decreed it; and the High Court, in second appeal, restored dismissal—prompting the present appeal.

3. Issues

The Court was called upon to decide: (i) whether the plaintiff established possession as on the date of suit to sustain a decree of perpetual injunction; (ii) whether the alternative claim for recovery of possession was maintainable absent pleadings on dispossession; and (iii) whether the widow’s possession in lieu of maintenance amounted to absolute ownership under Section 14(1) of the Hindu Succession Act.

4. Petitioner’s arguments

The appellants contended that the plaintiff’s name in revenue records demonstrated ownership and that the defendant’s possession, if any, was merely hisadari or permissive. It was argued that the High Court erred in recognising the widow’s maintenance claim and in overlooking the plaintiff’s asserted fractional share. The appellants urged that the alternative prayer for recovery of possession ought to have been entertained, particularly given the family relationship and the alleged absence of proof that the land had ever been granted for maintenance.

5. Respondent’s arguments

The respondents submitted that the plaintiff failed at the threshold by not proving possession on the date of suit—an essential ingredient for injunction. As to recovery of possession, they emphasised the absence of foundational pleadings: no date, manner, or circumstances of dispossession were pleaded. On merits, the respondents maintained that the widow’s right to maintenance was a pre-existing right under Shastric Hindu law, that the land was granted in lieu thereof, and that Section 14(1) enlarged her limited interest into absolute ownership after 1956.

6. Analysis of the law

The Court reiterated settled principles governing suits for injunction and possession. For perpetual injunction, possession as on the date of institution is indispensable. For recovery of possession, pleadings must disclose entitlement, the manner of acquisition, the date and mode of dispossession, and the illegality of the defendant’s possession. Evidence cannot substitute pleadings. The Court also analysed Section 14(1) of the Hindu Succession Act, emphasising its expansive sweep in converting a Hindu female’s limited estate—howsoever acquired—into full ownership when traceable to a pre-existing right such as maintenance.

7. Precedent analysis

The Court relied on authoritative guidance on pleadings and possession, particularly the decision in Maria Margarida Sequeira Fernandes v. Erasmo Jack de Sequeira, which mandates detailed, particularised pleadings to prevent false or speculative claims. On women’s property rights, the Court endorsed the consistent line of authority that recognises maintenance as a pre-existing right and applies Section 14(1) to enlarge the estate, rejecting narrow constructions that would defeat the remedial purpose of the statute.

8. Court’s reasoning

On facts, concurrent findings established that the plaintiff was not in possession at the time of suit. That alone defeated the injunction. Turning to recovery of possession, the Court found the plaint “bereft of required details” on dispossession; hence, the alternative relief was untenable. On title, the Court upheld the High Court’s conclusion that the land had been granted to the widow in lieu of maintenance and that Section 14(1) operated to perfect her title into absolute ownership. The First Appellate Court’s approach—shifting the burden to the defendant without the plaintiff discharging his own—was found erroneous.

9. Conclusion

The Supreme Court affirmed dismissal of the suit. It held that deficient pleadings cannot be cured by evidence, that injunctions cannot issue without proof of possession, and that a Hindu widow’s maintenance grant matures into absolute ownership under Section 14(1). The appeal was dismissed with no order as to costs.

10. Implications

The judgment reinforces procedural discipline in civil litigation, underscoring that precise pleadings are foundational to reliefs of injunction and possession. Substantively, it reiterates the protective and enlarging intent of Section 14(1), strengthening women’s property rights where possession flows from maintenance. Trial and appellate courts are reminded to respect the structure of suits and the burden of proof, lest decrees rest on conjecture rather than pleaded facts.

Case Law References

- Maria Margarida Sequeira Fernandes v. Erasmo Jack de Sequeira – Set out stringent requirements for pleadings and proof in possession disputes; applied to reject reliefs absent particulars.

- Section 14(1), Hindu Succession Act jurisprudence – Recognises maintenance as a pre-existing right; limited estates acquired in lieu thereof ripen into absolute ownership.

FAQs

Q1. Is possession on the date of suit mandatory for a perpetual injunction?

Yes. Courts require proof of possession as on the date of institution to grant a perpetual injunction.

Q2. Can a court grant recovery of possession without pleading dispossession details?

No. A plaint must specifically plead the date and manner of dispossession and the illegality of the defendant’s possession.

Q3. Does land given to a widow for maintenance become her absolute property?

Yes. If traceable to a pre-existing maintenance right, Section 14(1) of the Hindu Succession Act enlarges the interest into absolute ownership.